Introduction to the Wicked Problem

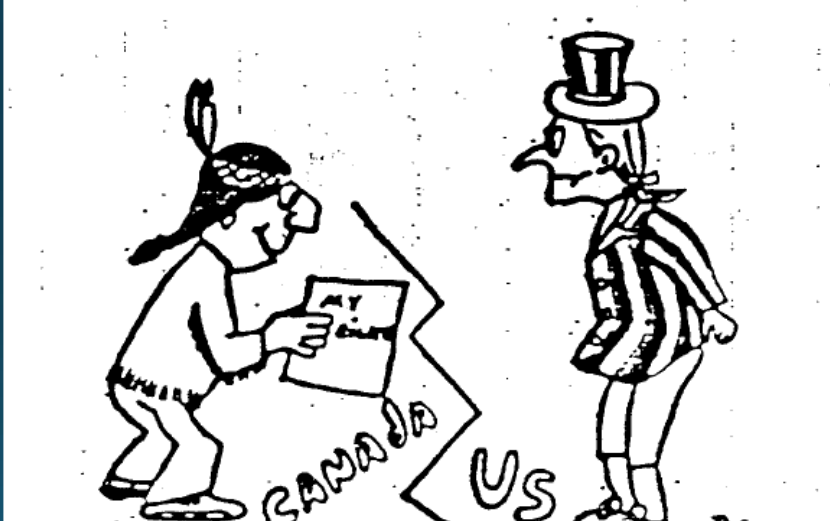

Eagle Wing Press October 1982

The countries of Canada and The United States of America are split by a theoretical political boundary which is reified by institutional structures which attempt to control cross-border movement and dictate and enforce the terms of occupation allowed within a given country’s borders.

The 1794 Jay Treaty – an agreement between the U.S. and Britain which arose in begrudging attempt to placate the latter following America’s independence – bore nested within a provision allowing for the free movement of North American Natives across the international borders separating the U.S. and Canada (U.S. Mission to Canada, n.d.; “John Jay’s Treaty,” n.d.).

This right to free movement was eventually granted to individual bearers of Indian Status, which is assigned under Canada’s Indian Act – a condition unlikely to be met by most U.S.-born Natives (“Border Crossing,” 2003; U.S. Mission to Canada, n.d.; “Background on Indian”, 2018).

So, while rights to cross-border travel for holders of Indian Status have been codified into U.S. legislation, Canada has refrained from any reciprocal legislative validation of cross-border rights for American Natives, partly on the basis that The Jay Treaty was effectively overturned by the Britain-U.S. War of 1812 (Francis, 2024).

The “wicked problem” here concerns the issue of how exactly to facilitate the reciprocal adoption of Native rights under the Jay Treaty within Canada. Such an adoption would entail the granting of Native populations within the United States the right to freely live, work and travel within Canada.

The Jay Treaty, in a sense, stands ‘grandfathered’ in to U.S. legislation, resulting in the incorporation of cross-border Native rights as a routine, familiar process to which the American public have become acclimated – to the extent they are aware of it (“Border Crossing,” 2003, U.S. Mission to Canada, n.d.). On the other hand, because the Jay Treaty has never been validated by Canada, to enact its reciprocal adoption in the present would presumably entail its reception as a novel prospect, subject to the evaluations and fears of both Native and non-Native Canadians.

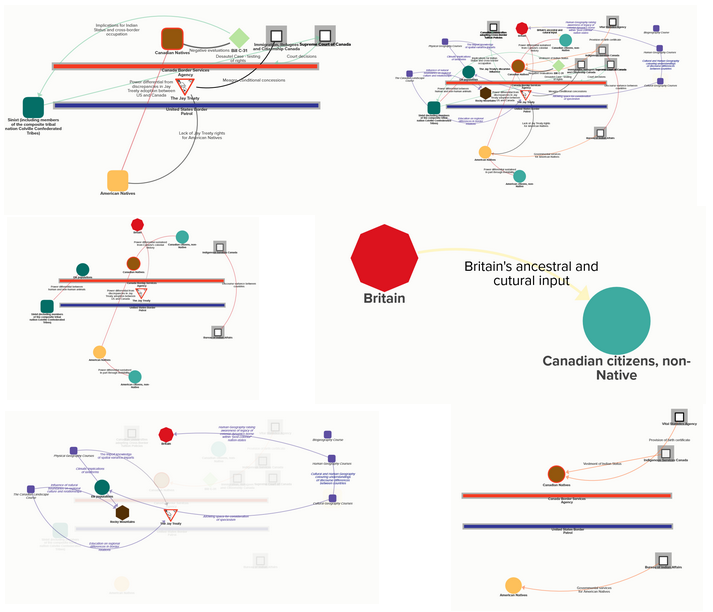

To aid in exploring the complexity of this problem, I created a map which attempts to locate and characterize the actors and institutions involved in a spatial formation of rough geographic correspondence, with a variety of colour-coded connections formed to characterize the nature of the processes involved.

The Jay Treaty systems map, viewed in “full.”

The placement of elements (the term Kumu uses to define map features) upon the systems map are generally roughly correspondent to actual geographic location. In cases in which a feature refers to a broadly dispersed subject – such as national populations – I attempted to place the feature at an approximate center between the locations in which they are most concentrated; for instance, the American Natives element was placed through reference to the largest U.S. Native populations being sited within California and Oklahoma.

Although text captions have been attached to each connection to summarize in a few words the nature of the relationships between elements indicated, each connection and element can also be clicked to produce more detailed information.

Elements were assigned differing symbols, essentially on the basis of intuitive association, to indicate their category:

Animals – in this case largely human animals – are symbolized with circles, to indicate a sort of perceived roundness, mutability, and complexity of their character relative to the more rigid and bureaucratic structures represented by most of the other elements included within the map. Colours assigned to differing categories are intended to indicate geographic distribution; for instance, proximity to moister, greener, more forested areas is indicated by green, greater proximity to drier areas is indicated by brown and yellow.

There are many institutions shown, mostly governmental, represented by black-bordered white squares.

Native bands – here limited to the Sinixt – are assigned Kumu’s “pill” symbol, indicating here a sort of gradient between the roundness of living organisms and the relative square rigidity of bureaucratically defined groupings of such.

Britain is assigned an octagon symbol as a representation of the historic outward colonial radiation of the British Empire towards the world’s varied reaches, including what is now known as North America.

The Jay Treaty is symbolized as a triangle pointing downward to the U.S. (“South” on the map) to indicate that, as it stands, the Treaty allows only the right to freely live, travel, and work within the U.S. for Canadian holders of Indian Status, with Canada heretofore choosing to not assign a correspond right to live, work, and travel within Canada to American Native tribal members.

Legislation, here limited to Bill C-31, is symbolized by a four-sided diamond shape, with the multiple points indicating the multiple implications borne by legislation in converse with varied actors and processes.

Finally, landforms – the border-spanning Rocky Mountains being the map’s sole example – are symbolized by a jagged hexagonal shape of rocky implication.

Colour-coded connections – of ancestral influence, power differentials, bureaucratic processes, impact gaps, and levers of change – enact a characterizing cast upon elements, linking them together in a variety of patterns, which are additionally interrelated with a personal scholastic connection scale which stresses my own particularity of reference point and though process in the map’s creation.

The Jay Treaty map, broken down by category of connection

While the full view of the systems map with all elements and connections included can grant the mapped system an illusion of relative comprehensiveness, breaking the map down by category of connection can better indicate the spatial trends and missing points of particular themed groupings of actors and processes.

Ancestral Influence

A single yellow connection indicates an ancestral influence, such as that of Britain on North America. This was a partial attempt to integrate a wide-range temporal scale within the mapped system. The colonial dynamics of Britain’s control over portions of North America sets the stage here for the figuring of power differentials within the system’s dynamics:

Power Differentials

Here we focus on red connections, which indicate identified power differentials between actors. I would note that many of these identified power differentials – such as those identified between Native Canadians and non-Native Canadians, and Native Americans and non-Native Americans, would tend to also correlate with, or speak to, some sort of impact gap. I would consider the relationships of power indicated here to flow under the energy of reverberating but fluid dynamics, which are clasped and corralled by the structural rigidity of routine bureaucratic processes:

Bureaucratic Processes

Orange connections indicate what are essentially routine bureaucratic processes undertaken in navigation of the Jay Treaty, the general character of which is one of compliance to the terms of the respective governmental powers of Canada and the U.S. The routine processes described here give way to more novel, paradigm-shifting levers of change, which act to address impact gaps:

Impact Gaps and Levers of Change

Impact gaps within the map represent missing connections with direct applicability to the wicked problem of reciprocal Jay Treaty adoption by Canada, whether engendered through ignorance or deliberate choice. For each impact gap an attendant lever of change is proposed to address and mend the impact gap. Green connections here indicate past levers of change, which can also involve bureaucratic processes, albeit of more unique, potentially precedent-setting character, such as the R. (the Crown) v. Desautel case. They constitute levers pulled to set forth notable changes in the figuring of the Jay Treaty within North America, and can serve as examples indicative of what proposed levers of change could or should look like – to draw from and build upon.

Scholastic

Geography and Environmental Studies course components are placed off to the side, as if on the sidelines, ungoverned by the quasi-geographic logic of the map’s remainder. They wear a regal, scholastic purple and are symbolized with what Kumu defines as a pill-shape, for different reasons than why I chose to use the shape for Native bands; just the simple implication that educational institutions provide “pills” to swallow. Connections are also purple, with their attendant captions placed in purple italics to distinguish them from the other connections and connection-captions. Here, the elements I specifically connected to course content are highlighted, but remaining elements also appear in faded form, to express that course learnings also inform my understanding of the mapped system’s whole, albeit possibly in a less direct manner.

Conclusions in light of the preceding

This website presentation allowed for interactive engagement with the Jay Treaty systems map, with separate “views” intending to indicate distinct patterns of category-specific processes and impact gaps within the system, in addition to amplifying the presence of missing points unacknowledged by my own map-making process. Further, the incorporation of semi-geographic correspondence in the placement of elements within the map allows an impression of how spatial patterns of influence, process, and actor agency differ between different categories of connection. Potentially, this multiple-view geographic approach further refines the potential for systems maps to aid in the collation and analysis of issues, and the delineation of their particular parameters and bounds.

Past levers of change have enacted meaningful adjustments to processes of cross-border movement and occupation for U.S.-born Natives within Canada, but the vast discrepancy in access to Jay Treaty rights between Canadian and American Natives necessarily creates a situation in which the onus for substantial change largely falls upon the more contextually privileged party – here, Canadian Natives, who stand in a position of relative advantage relative to American Natives in this regard while simultaneously occupying a marginalized position – generally possessing little power or influence – within Canada. Subsequently, it appears that the success of future levers of change would stand conditioned not only upon the altruistic enthusiasm of Native Canadians in advocating for the rights of Natives south of the border, but on eventual shifts in legislature to be put into force by Canada’s largely non-Native hegemonic powers, with attendant problems of attaining social license among the greater Canadian public.

References for Introduction

Background on Indian registration. (2018, November 28). Government of Canada. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1540405608208/1568898474141

Border Crossing Rights Under the Jay Treaty. (2003). Pine Tree Legal Assistance. Retrieved October 28, 2025, from https://ptla.org/border-crossing-rights-under-jay-treaty

Francis, J. (2024, February 8). Want to work in the U.S. through the Jay Treaty? Some say process is confusing, frustrating. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/indigenous-jay-treaty-work-us-1.7103716

Free Passage Rights Of North American Indians Born In Canada Under The Jay Treaty And 8 U.S.C. § 1359. (2024, June 7). Legal Services of North Dakota. https://lsnd.org/free-passage-rights-of-north-american-indians-born-in-canada-under-the-jay-treaty-and-8-u-s-c-%C2%A7-1359/

John Jay’s Treaty. 1794–95. (n.d.). Office of the Historian. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1784-1800/jay-treaty

U.S. Mission to Canada. (n.d.). First Nations and Native Americans. U.S. Embassy & Consulates in Canada. https://ca.usembassy.gov/first-nations-and-native-americans/

References for Kumu Systems Map

Bill C-31. (2025, August 11). The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved October 28, 2025, fromhttps://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/bill-c-31

Border Crossing Rights Under the Jay Treaty. (2003).Pine Tree Legal Assistance. Retrieved October 28, 2025, fromhttps://ptla.org/border-crossing-rights-under-jay-treaty

British Empire. (2025, September 29). Britannica.https://www.britannica.com/place/British-Empire

Canada Border Services Agency. (2025, October 27). Government of Canada. Retrieved October 28, 2025, from https://www.cbsa-asfc.gc.ca/menu-eng.html

Curry, J., Donker, H., & Krehbiel, R. (2014).Land claim and treaty negotiations in British Columbia, Canada: Implications for First Nations land and self-governance. Canadian Geographer, 58(3), 291–304.https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12088

Ethnic and cultural origins of Canadians: Portrait of a rich heritage. (2017, October 25). Statistics Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/98-200-x/2016016/98-200-x2016016-eng.cfm

Getting here. (2025). Supreme Court of Canada. https://www.scc-csc.ca/contact/directions/

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. (2021, June 17). Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-northern-affairs.html

Indigenous Mobility and Canada’s International Borders: Reflecting back and looking forward. (2024). Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/publications-manuals/indigenous-mobility.html

In the Supreme Court of British Columbia. (2011, January 2). Sinixt Nation. https://sinixtnation.org/files/Marilyn-James-Affidavit-2—Janaury-2011.pdf

John Jay’s Treaty. 1794–95. (n.d.). Office of the Historian. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1784-1800/jay-treaty

O’Shea, Michael. (2022). 225 Years in the Making: How Canadian Universities Honour the Jay Treaty Through Cross-Border Tuition Policies. University of Victoria. https://biglobalization.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Research-Brief_JBTA_Policy-Brief-February-2023_Final.pdf

O’Shea, Michael. (2024). Honouring the Jay Treaty: Cross-Border Tuition Policies at Vancouver Island University and the University of Saskatchewan. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto). University of Toronto TSpace. https://utoronto.scholaris.ca/items/e05ad9a7-85c9-478f-976c-5bca17b121ed

Research Reveals America’s Attitudes about Native People and Native Issues. (2018, June 27). Cultural Survival.https://www.culturalsurvival.org/news/research-reveals-americas-attitudes-about-native-people-and-native-issues

Supporting cross-border mobility for Indigenous Peoples. (2024, October 10). Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/news/2024/10/supporting-cross-border-mobility-for-indigenous-peoples.html

The Desautel Decision. (n.d.). Sinixt Nation. https://sinixt.com/the-desautel-decision/

The Environics Institute for Survey Research. (2016). Canadian Public Opinion on Aboriginal Peoples. The Environics Institute. https://www.environicsinstitute.org/docs/default-source/project-documents/public-opinion-about-aboriginal-issues-in-canada-2016/final-report.pdf?sfvrsn=30587aca_2

U.S. Mission to Canada. (n.d.). First Nations and Native Americans. U.S. Embassy & Consulates in Canada. https://ca.usembassy.gov/first-nations-and-native-americans/